Reviews

Peripheral Visions – A History

Digital technology and the creative process

In 1999 I had a moment of revelation stuck in traffic in the rain and dark of a rush hour on the London North Circular. At that time I was producing paintings and drawings of the human body. It had been a difficult personal time with several bereavements and I was pondering the nature of the body, physicality, thought and memory.

Working in my studio I thought constantly about the past and people no longer around. What I remembered changed daily, no memory seemed accurate, no drawing or painting precise enough. I wanted to depict the ephemeral, but felt heavy handed, I wanted lightness and I couldn’t shed the obvious baggage and break though to this light.

Water

24th November 2010 – 22nd December 2010

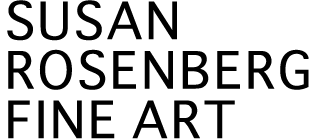

Susan Rosenberg’s flower paintings (shown in her previous exhibition, Altitude) blend energy and bravura with structure and balance. Spontaneity and impulse persist in her deeply considered designs. Colour and line toss, play and respond as in a dance. Now, in her water paintings, she has moved from quasi-abstraction to a greater naturalism, an unusual trajectory. The theme of water is a difficult and bold one to pursue, both technically and because of the weight of tradition, but it has called forth Susan’s creativity brilliantly. As always, her art gives delight in the complementarity she achieves between strong lineaments of design and a lyrical interplay of colours. In the water paintings she has introduced a more highly nuanced application of paint. There is narrative drama in these pictures but also a stylised, even ritualised, quality arising from her use of gold. Susan’s art, for me, is a consolation in difficult times and an added joy in happy times.

Rt Hon Lord Howarth of Newport

Altitude

Susan Rosenberg’s latest paintings, with their vivid colour and movement, can easily be appreciated as direct – often joyful – evocations of the act of walking through mountain ranges at high altitudes, inspired by journeys undertaken through South Africa’s Drakensberg and Cape Mountains, the Sierra Nevada in California, the Olympics in Washington State, and the Alps and Dolomites in Europe. But, as with her previous explorations of the human body and still life, the paintings also reflect a more subtle, layered and internal striving for various forms of balance and poise.

Then and Now

Many viewers who have followed Susan Rosenberg’s work over three previous solo exhibitions at the Millinery Works will note a marked move towards abstraction in her new paintings – entitled “Then and Now”.

On one level, restless move and change seems to be a feature of her work over the past twenty years, with her prodigious output encompassing the human figure, reinterpretations of still lives, and a regular return to references to fragments of nature. But look behind the change, and there are a number of constant elements running through Susan’s work, which provide a strong core of continuity.

Still, Life

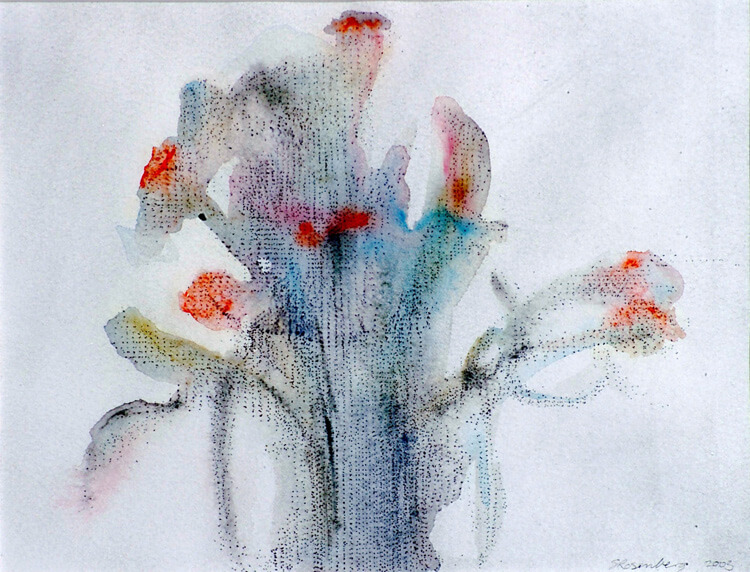

“Memory isn’t always accurate,” says Susan Rosenberg, at the very start of our conversation about her new exhibition; and it’s an appropriate place to begin, given that her evocative work – which draws on her life – is about what we forget, as well as what we remember. “You might see a face in the crowd, and suddenly you are reminded of someone – but what you remember might be blurred, even if it feels very vivid.”

She has always been interested in how she might visually express those fragments of memory: whether in the ethereally anonymous human figures of her last exhibition, or her latest work, of plants and flowers. As with the figures, these are not flowers that can be named and pinned down, specified or identified. “They come from the recesses of the past,” she says, “from travelling, perhaps, when you glimpse a field from a train, or maybe the flowers that you see at wedding. They get tangled up with previous experiences – flowers at births, or marriages, or deaths – the colours in the threads of memory.”

Many viewers who have followed Susan Rosenberg’s work over three previous solo exhibitions at the Millinery Works will note a marked move towards abstraction in her new paintings – entitled “Then and Now”.